German gemütlichkeit: The 25th Doll Collection Dinner

Flavors from the old country, sweet meals, and connecting with ancestors

Dear readers and friends,

As the calendar year comes to a close, I want to offer another family dinner story that is both a culinary adventure and close to home.

We started our Doll Collection Dinners over two and a half years ago and have cooked twenty-five meals from twenty-five different countries: Poland, Yugoslavia (Serbia), Denmark, Finland, Mexico, Venezuela, Malawi, Zimbabwe, England, Canada, The Netherlands, Israel (Palestine), Greece, Australia, New Orleans (USA), Italy, Hungary, India, Malaysia, France, St. Kitts, Russia, Japan, and Germany (twice).

This family project started after a spring break visit to my parents’ house in Georgia, where my doll collection had been filling a large bookshelf and gathering dust. We returned to Wisconsin with two bins of figurines, puppets, marionettes, ceramics, and wood carvings from around the world. The first “doll” was bought in 1978 in Poland and brought home by my father as a souvenir for three-year-old me. His travels continued and the collection grew to more than seventy generally well-dressed human figures. They are all labeled with a number that corresponds to a list noting where they were made and in what year they were purchased. Each doll is unique and many are truly beautiful works of local craft and design. But what I like best, now, is that they invite me to journey in my dad’s footsteps with my own daughters, to enjoy stories and flavors that widen our imagination and understanding. This, I think, is the highest achievement one could hope for a souvenir and is the true legacy of having a father, or in the case of my kids, a grandfather, ready to explore every corner of the world.

He isn’t interested in tallying countries visited, but Germany is the place my father has been most often. He studied and learned to speak German as an adult and, as a university professor, he eventually lectured in German when he was working there. I lived in Germany three times as a tag-along kid and love the country and the language. I would never have said that I love the food, but when I learned that

, who wrote the beloved “Classic German Baking” book announced she was writing a companion with the very best recipes for classic German cooking, I bought an advance copy.German food is not generally considered very exotic to Americans. “German food is also American food,” writes Weiss in her introduction, and “German food is also Jewish food.” Wikipedia explains there is a German belt that extends across the United States from eastern Pennsylvania, where many of the first German Americans settled, to the Oregon coast. The arrivals before 1850 were mostly farmers who sought out the most productive land, where their intensive farming techniques would pay off. After 1840, many came to cities, where German-speaking districts emerged.

Truth is, there are German foods I love. I make homemade Spätzle noodles somewhat regularly, and living in the “German belt” that passes through Wisconsin, we eat plenty of Wurst. I even own a mallet for flattening chicken so that it can be covered in breadcrumbs and fried as a Schnitzel.

Germans are credited for introducing the Christmas Tree and the Christmas Market to America, so maybe it’s natural that around the winter holidays in particular, I get homesick for Germany’s desserts. It’s a cultivated heimweh that I lean into heartily and happily load up on imported Stollen and gingerbread from Trader Joe’s.

German immigrants introduced the New World to hotdogs, hamburgers, and potato salads. I haven’t read this anywhere but I also suspect the Deviled Egg is a German invention. And I’d bet money that the origin of the ubiquitous Chicken Tenders that American kids survive on at restaurants is thanks to some sweet young German women working in a colonial American tavern who knew how to pound meat into tenderness, then dip it in eggwash and stale bread to fry up a hearty dinner customers would come back for time and again. I ate schnitzel at every restaurant I ever went to as a kid in Germany, and now my daughters carry on by testing out versions of chicken tenders on menus that are high-brow, low-brow, and with menus that claim no connection to German-Americans

Weiss writes, “if I had to pick any one word to describe German food, I think nostalgic is the word I’d choose.” It’s also, she says, “the purest kind of comfort food.” The German essayist Elke Heidenreich tells the story of having eaten chicken feet and pigs ears and all manner of strange food for a week in Beijing when an American asks her to join him at the Hofbräuhaus for brats with mustard, pretzels and beers. She is chagrinned by the modern Chinese waiters in Lederhosen, but thrilled to have a meal that doesn’t show up as a whole animal on the table.

I’m grateful for a personal relationship with Germany grounded in real-life experiences and memories that start when I was six years old, but like 12% of Americans, my DNA connection goes much deeper. Our people were among tens of thousands who came from villages along the Rhine River in Bavaria, as well as from cities in the north of Germany, to settle along the Ohio River in Cincinnati. So while my family immigration story is not unique, I am grateful to have wandered many German villages and cities, to have eaten home-cooked food in German kitchens, and I can laugh at the nuances of the language (Elke Heidenreich’s books are pretty much on loop in my Audible).

The German words my kids know best are Kaffee und Kuchen. When we are having an ideal weekend, afternoons include coffee and cake. Weiss writes that German’s have a sweet tooth and her book includes a whole section on sweet main courses — puddings and casseroles and fried doughs with fruit toppings. She says this is “one of the more idiosyncratic traditions of German food culture” and goes on to say that the recipes in that section could be the meal or the dessert. Makes sense to me.

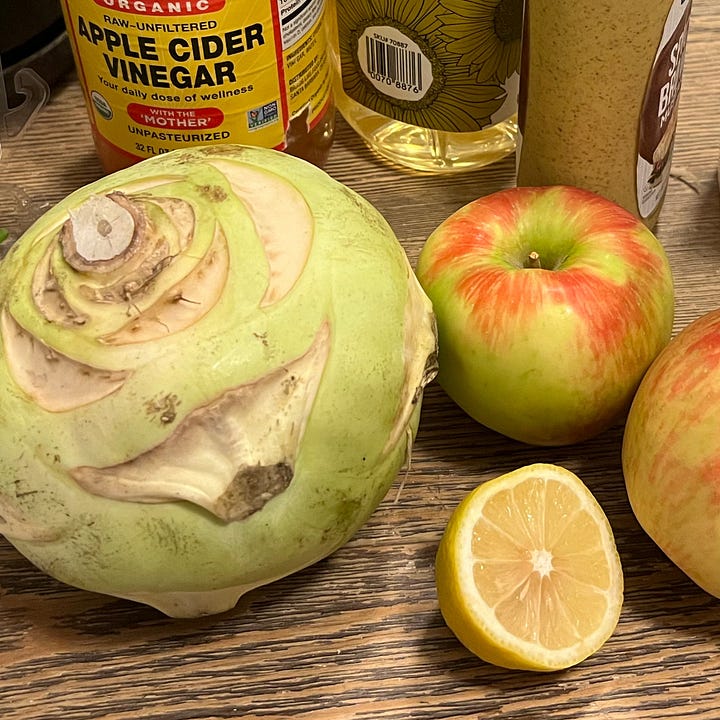

Schokopudding is a childhood favorite that I still love, and I’ll share Weiss’s simple and staple recipe for chocolate pudding with vanilla sauce below — it’s not quite as sweet as American versions and so easy it makes the boxed stuff seem stupid. But what we made for this German Doll Dinner pulled from other German traditions: potatoes, eggs, cabbage, kohlrabi, apples, vinegar, and lots of whole grain mustard.

While German cooking is hearty and often meaty, we went meatless for this meal.

Our Menu

All recipes from “Classic German Cooking” by Luisa Weiss:

Buttermilchgetzen / Potato-Buttermilk Casserole

Eier in Senfsoße / Eggs in Creamy Mustard Sauce

Kohlrabisalat mit Apfel / Kohlrabi-Apple Salad

Schokoladenpudding mit Vanillesoße / Chocolate Pudding with Vanilla Sauce

Schokoladenpudding mit Vanillesoße / Chocolate Pudding with Vanilla Sauce for 4-6 servings (recipe by Luisa Weiss)

Ingredients for the pudding:

3.5 oz semi-sweet chocolate (50% cacao)

2 cups whole milk

1 tbsp sugar

1/4 tsp salt

1 egg yolk

1/4 cup cornstarch - I found this to be too much, resulting in a stodgier pudding than I like. I’ll probably reduce it next time.

Ingredients for the vanilla sauce:

2 tbsp plus 1 tsp sugar

2 cups whole milk

1/4 tsp salt

1/2 vanilla bean, split and scraped

2 tbsp cornstarch

2 egg yolks

For the pudding, whisk 1/4 cup of milk with cornstarch and the egg yolk until there are no lumps. Set it next to the stove.

Put 1 3/4 cups of the milk in a saucepan with the chocolate, sugar, and salt. Melt on medium heat while stirring.

Once the chocolate milk is warm with no lumps, add the cornstarch slurry in and turn up the heat a little. Whisk continuously until it’s thick and the whisk ‘leaves traces in the pudding.’

Pour the pudding into little cups or bowls and cover each with a piece of plastic wrap, pressing it against the surface so no air hits the pudding to make a thick ‘skin.’ Cool it to room temperature, then chill for a few hours.

For the vanilla sauce, it’s a pretty similar process, but you want the result to be saucier. Make the cornstarch slurry with 1/3 cup milk, cornstarch, and egg yolks.

Then heat 1 2/3 cups milk in a saucepan with the sugar, salt, and the split vanilla bean pod, along with the gooey black inner scrapings of the pod. You’ll heat the milk on medium-high. When it starts to bubble, turn it down to medium-low. Then slowly drizzle a ladleful of the milk to the cornstarch slurry as you whisk. You are tempering the egg yolks so they don’t curdle. Then pour this mixture into the saucepan of hot milk slowly, whisking constantly.

Turn the heat back up a bit, to medium. Keep whisking and cooking til it thickens, just a few minutes.

Weiss writes, “The traditional way to see if the sauce is ready is to stir the sauce with a wooden spoon, then remove the spoon from the pot and blow gently on the back of the sauce-coated spoon. If the sauce is ready, it will form the same of the petals of a rose.” So blow the spoon like a dandelion and see if the creamy coasting spreads out like a flower.

Then let it cool to room temp. This sauce will keep for a few days in the fridge and can be poured over pie, pancakes, puddings, etc.

I hope it’s yummy, or lekker! Enjoy!

Thank you, Jessica. Nice memories. I'm so glad you have enjoyed sharing these dolls with Willa and Zadie. I could not have hoped for anything more.

Love this post, Jessica. My family migrated to Australia from Germany in the 1950s. I grew up with many German traditions, especially around Christmas time. Now I try to keep these traditions alive and my own Christmas table.

Today I made stollen Blondies - a brownie texture without the yeast. They are delicious interpretation. I’ve also made Bethmännchen, speculaas and Elisen Lebkuchen.

It’s very hot here in Australia at the moment and I find myself thinking of Christmas last year, when I visited Germany for the first time, and experienced a winter Christmas with extended family.