Learning to Weave

The threads of life, the language of textiles, and handmade tortillas in Guatemala.

Dear friends and readers,

I make some of my own clothes and also do a bit of knitting, so sometimes I’m asked by other textile enthusiasts if I weave. I don’t, but I did once learn the basics. And I am delighted and fascinated by the fact that language about writing, and about life itself, uses words and metaphors that reference the making of cloth.

Learning to weave could be a metaphor for handling the threads of life with enough care to ultimately find comfort in the texture of community connections. Words like text and texture and textile obviously share a root, but you may not realize that a line of text references the word linen, the first fiber that humans cultivated.

The very oldest remnants of woven textiles were found in a cave by archaeologists in the Republic of Georgia. They are sophisticated weaves made from flax fibers that had been dyed turquoise, red, yellow, blue-violet, green, khaki, and pink. The plants were likely tended, then gathered, processed, and made into useful things, by skilled and knowledgeable people who were part of a culture that carried both the language and the stories to pass on these technologies.

When you think of those people living their daily lives over 34,000 years ago talking about their work and creations, it makes sense that the words for making textiles, with all their usefulness, symbolism, and personality, have evolved within the art of storytelling and rhetoric. Fabric and its component parts are a figurative stand-in for the very stuff of human life. If you want to read more on the subject, I really enjoyed The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History by Kassia St. Clair and will be publishing a longer article about linen in April. Stay tuned for that!

For many years, I subscribed to a lovely ad-free and inspiring magazine called Taproot with the alluring tagline “for makers, doers, and dreamers.” The pages full of stories opened windows into new ideas and left me feeling like a part of a something bigger.

The magazine is no longer published, but in that spirit I’ve decided to share my story of learning to weave. Like those Taproot articles about working with one’s hands to discover deep truths and personal understanding, writing “Learning to Weave” gave me some new insights about myself, my ongoing curiosity for the world, and all of our varied but interwoven paths.

Seeing in Full Color

The corner shop was a simple construction and built a step or two off the cobbled street. Soft light poured from the shop into the quiet village. It was getting dark and someone rode by slowly on a small horse.

The shopkeeper knew our teacher, a woman my girlfriends and I had just hired to instruct us on how to weave with a backstrap loom. The glass counter displayed the available stock, small bundles of thin, brightly colored string, and we were advised about the quantity we’d use the next day to make our very own Guatemalan weaving. After spending weeks in Mexico and the Guatemalan highlands, where women dressed colorfully in woven skirts and blouses called huipiles adorned with embroidered flowers, I’d become mesmerized by bold hues. In this landscape, I looked and felt like a tall, pale boulder in my drab khakis and white t-shirt that was by this point stained and dirty.

What I lacked in style I tried to make up for with smiling curiosity and optimism — I was inhaling the wild colors, imbibing the joy, swimming in the fresh unknown. Sleeping three to a single bed stuffed into a broom closet in a town with a name I couldn’t pronounce didn’t faze me. Nor bouncing along mountain roads in rickety old school buses with an overloaded backpack on my lap and sweat pouring from every pore. Not even getting detained at a jungle border crossing because my friend had lost the thin slip of paper that traced entry into this country, a county that had until very recently been bloodied by a civil war that was particularly brutal to women. It was all an adventure to my young mind and body. I had wide-eyed wonder on tap then.

Trying to choose, I became flooded with visions of some imaginary apartment someplace where I’d live someday. In my daydream, I’d embellish my future life with meaningful textiles from around the world. I wanted to pick just the right palette for future me.

I finally selected royal blue, red, purple, and green and the next day we met up with our teacher again in her kitchen/classroom/living room. It was a square space with windows of thin glass panes. Not every home had windows of glass, so I noticed them, and I noticed that our teacher wore glasses with thick, plastic frames. Later I wrote in my journal that I couldn’t remember having seen another indigenous Maya person wearing glasses. I reflected on her status in the community, probably a result of her business acumen.

The flyer advertising a chance to spend a day learning to weave on a backstrap loom had been tacked up on a bulletin board at our hostel. Since the 1960s, tourism to this lake at the base of three volcanoes had been significant but small-scale, just intrepid backpacker-style. When we showed up in 1997, the tofu taco joints were just starting to fire back up after 36 years of war.

My step-sibling made their way to Guatemala four years after me, as a college student to study Spanish. They then spent five months as an international human rights observer. Days were spent in communities not unlike where I learned to weave, mountain villages that had been tormented by two consecutive dictatorial regimes, offering simply a presence as people went about daily life as best as they could.

They remember watching the village children playing on a field that was going to be dug up soon. It was understood that there were hundreds or thousands of “murdered bodies” under the kids’ feet. That was in 2001 and 2002. Many court cases were underway then in Guatemala. Mass graves were being opened and survivors were getting the chance to identify their relatives from the remains. Volunteer witnesses were part of the process. My sibling wrote later for the college newspaper that “people seemed intent on getting the work done” at the exhumations and there were few tears. But at the funeral ceremonies, which lasted for several days at a time, families “prayed and cried, prayed and cried.”

Our weaving lesson was taking place in a village that was a short walk from the tranquil shores of beautiful Lake Atitlán. Women washed their hair and clothes in the stream-fed waters, strong smiles filling their faces as their soft laughter tickled the sun-sparkled surface. A few months earlier, I’d read about the Peace Accords of 1996 from a comfortable campus classroom. I’d learned that in 1950, over 71% of Guatemalans had voted in the country’s second democratic election. The U.S. did not like the winner’s agrarian reforms. He was considered a communist threat and the U.S. chose to protect the interests of the United Fruit Company. A U.S.-backed coup in 1954 led to decades of psychological warfare, torture, and genocide. Somehow life among the volcanoes went on.

Sitting on the concrete kitchen classroom floor, we were instructed first in how to create the warp by looping our chosen colors around nails on boards. Young children and chickens came and went. The teacher’s adult daughter worked alongside us on a larger project that was well underway. Mid-morning, she paused her weaving to make tortillas. She quietly patted masa between her palms, cooked the small rounds of dough one by one, then crumbled a pinch of salt in the center of each warm cornmeal patty. The snacks were offered around without words.

Using the most basic Spanish and a smile, I attempted to show my gratitude. Our teacher’s Spanish was better than mine, but it wasn’t clear how much Spanish the daughter spoke.

My travel companions spoke fluent Spanish and were more loquaciously appreciative. One of them accidentally commented on the little pile of salt crystals that had been sprinkled on her tortilla, probably an especially generous quantity for a paying guest. She quickly read our hosts’ confused faces and realized her blunder. She doubled back and tried to explain the American concern about sodium and high blood pressure to the highland natives of an ancient Mayan culture. There are many Mayan languages spoken around Lake Atitlán but these women who had probably never seen a blood pressure cuff or had regular visits to a medical clinic knew no words for our problems.

Work resumed. We were tucked into the individual looms we had built for ourselves from colorful strings. The top of the loom was hooked into nails sticking out of the ceiling beams and our bottoms were cradled by the other end. Once we’d been strapped in, not much talking was necessary. Mother and daughter wove, too, working on much wider and more complicated designs that would probably be sold in a tourist market. The gentle knocking of wooden heddle sticks and shuttles created a pleasant quiet. We worked until it got late and very dark outside.

I squint into the memory of that kitchen classroom now and see how the experience has become an intangible component of who I am, a stand-in for the stuff of life that no archaeologist would ever find. It is only a colorful feeling, the texture of a memory, the lines of this wandering tale. Stretch marks have faded into something like humility embellished with a few thin threads of wisdom.

No, I am not a weaver, but I enjoyed the productive and relaxed activity of weaving very much. In fact, I kept weaving as we traveled onward, hooking one end of the portable loom onto curtain rods or hammock hooks in the hostels and homestays around Guatemala, Honduras, on the island of Utila in the Caribbean, and then back in Mexico. The royal blue, green, purple, and red threads became a four-inch by five-foot strip of fabric, which I eventually used to make a tablecloth. It was one of the first decorative elements of my adult life, a life I could only vaguely conjure as I made choices in a little corner shop at the base of a volcano. It is stained now, as happens to t-shirts and tablecloths.

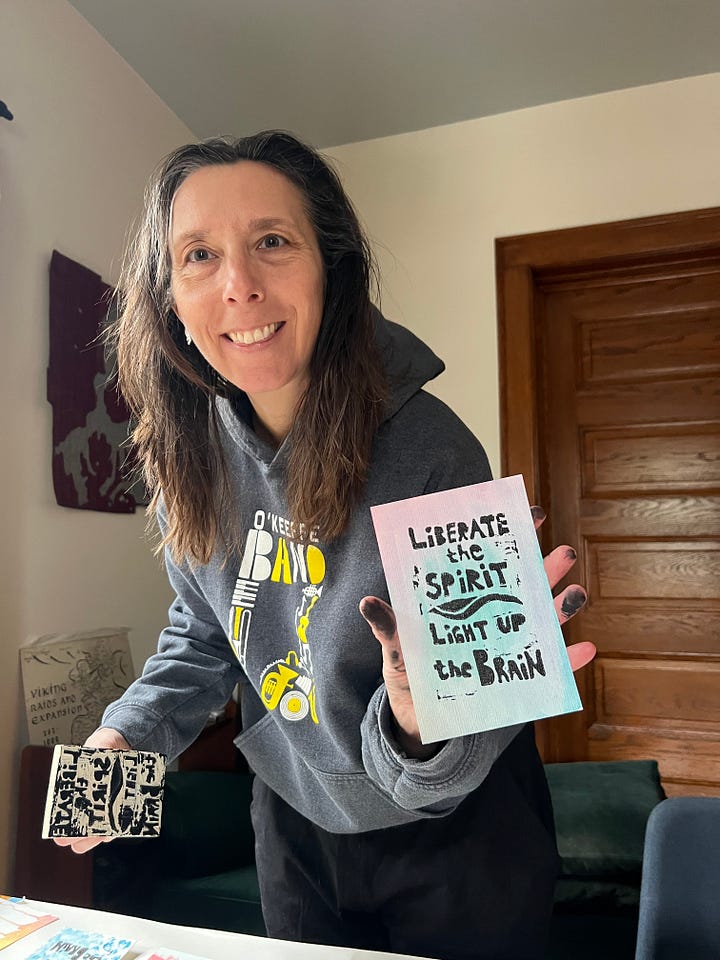

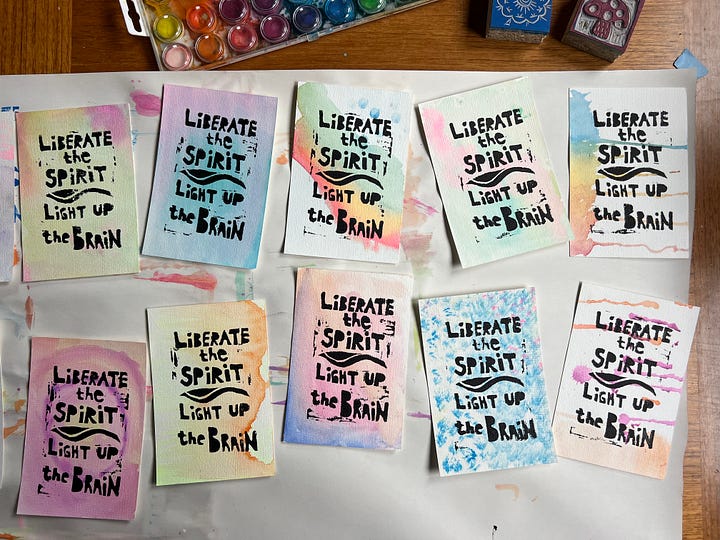

Thanks to every single one of you for wandering with me, and a BIG SPECIAL THANK YOU to my paid subscribers, who sometimes get handmade love letters in their real snail-mail boxes. My daughter helped by painting the watercolor backgrounds of these postcards, then she picked up the camera (without my prompting) and took some really nice photos.

Thank you to all the helpers, makers, and dreamers! As the novelist Tom Robbins once wrote, “We are in this life to enlarge the soul, liberate the spirit, and light up the brain.”

Hi Jessica, I forwarded this writing to my granddaughter, Julia, who is a junior in college and she is a fiber artist and works on a loom. I knew she would enjoy your writing about your weaving experience.

Peace, Jan

Love it! It was really interesting